The discovery

The renown ancient Armenian monastery complex ‘Tzarakar’ has been discovered near the village of Chukurayva, 5 kms south-east of the fortified town of Kechror, modern-day Turkey (the old Gabeghiank district, Ayrarat province of Greater Armenia). What remains of it are the interior cut-in-rock structures, the exterior buildings are irretrievably lost.

The monastery consists of a church which has several entrances connected with each other, at least six chapels and other adjoining buildings. It is remarkable for its very interesting structure and extended lapidary inscriptions. Despite it, however, until recently neither specialists nor topographers ever paid any attention to it.

It was only in 1999 that the monument was first visited by a specialist, namely Scottish researcher Stephen Sim, who took photographs of it and made its schematic plan. Later it was visited by seismologist Shiro Sasano, who published a small-scale research work on it together with several photographs he had taken there in 2009.

In this way, these two foreign researchers discovered the cut-in-rock monastery and made it known to the scientific world. They, however, failed to find out its name and called it after the adjacent village presently inhabited by Kurds.

Understanding the importance of conducting comprehensive studies in the monastic complex, in 2010 the members of Research on Armenian Architecture conducted scientific expeditions and revealed a lot of information relating to it. The available sources attest that this newly-discovered monument complex is the monastery of Tzarakar, which is mentioned in medieval records, and the location of which remained unknown until very recently.

Among others the following facts give grounds for identifying the newly-found monastery with Tzarakar:

As is known, Tzarakar was one of the renowned monastic complexes in medieval Armenia, but in the course of centuries, it lost its glory and significance and was consigned to oblivion to such an extent that in our days even its location remained obscure.

Late 19th century, Gh. Alishan used the available sources to point to the area where the monastery could have possibly been situated: “…Tzarakar, which is mentioned in some works by historiographers and geographers, is known to have stood in a naturally impregnable site in the vicinity of Kechror: first of all, a cut-in-rock monastery was erected…”

S. Eprikian came to the same conclusion: “Supposedly, a monastery of this name and a village used to be situated near Kechror, Gabeghenk District, Ayrarat [Province].”

The colophon of an Ashkharatsuyts (a geographical work), dating back to 1656, also confirms: “…the district of Gabeghenits and the castle of Kaput also called Artagereits—the town of Kechror is situated there together with the cut-in-rock monastery of Tzarakar, where Archimandrite Khachatur Kecharetsi’s grave is found…”

This passage reveals two facts of the utmost importance: firstly, Tzarakar Monastery was cut in the rock, and secondly, most presumably, it was situated not far from the town of Kechror. That Khachatur Kecharetsi, a worker of education and a poet who lived between the 13th and 14th centuries, was buried somewhere near Kechror, is also attested by the following note on a map of 1691 compiled by Yeremia Chelebi Kyomurjian: “Town of Kechror, bordering on Basen, and Archimandrite Khachatur’s grave.” These two records clarify that the monastery of Tzarakar was truly located near the fortress town of Kechror.

Besides written records, the etymology of the toponym of Tzarakar was also of importance to its identification. Every visitor may easily see that the structures of the monastic complex are cut into quite friable masses of rock which are naturally striped and have certain coloring, looking like the parallel circular lines showing the age of a cut tree—evidently, the name of Tzarakar, the Armenian equivalent for Tree Stone, is conditioned by this resemblance meaning a monastery cut into a tree-like stone.

Inscriptions in the monastery

The primary sources casting light on the historical events connected with Tzarakar are three lapidary inscriptions preserved in the monastery, though they have reached us in a very deteriorated state. The first of them is carved on its western facade: it is marked with irregularity of writing, for its 11 lines and the size of its letters do not seem to have any order. It is a donation inscription dated 952 mentioning Tiran, spiritual shepherd of Vanand District, and Bishop Sahak Amatuny.

Translation: This is written by Tiran, spiritual shepherd of Vanand… shahanshah… gardener… St. Grigor … for my soul’s sake… may those who object to this writing be cursed by God, as well as …Tiran and Bishop Sahak Amatuny… Hakob… may he who fulfills the commands be blessed and he who raises an objection to this writing be damned and fall into the devil’s hands.

Another extended donation inscription of 17 irregular lines, dating from the same period, i.e. 10th century, has come down to our days in a semi-distorted state. It is engraved on the northern wall of the same church and is especially important as it mentions the founder of Vanand (Kars) Kingdom, Mushegh.

Translation: …St. Grigor …handwriting… For God’s sake… Armenian King Mushegh… the monastery and churches on the order of Father… after my departure… is cursed… those who carry out the orders… may be blessed…

The third inscription, dated 952 like the first one, is even more distorted and consists of at least four lines (we are not sure about the existence of the fifth one). A considerable part of it has already been irretrievably lost due to natural corrosion and certain vandalistic actions probably committed by those searching for treasure in the monastery. At present only the following is legible from the inscription:

The remnants of an inscription 952AD., originally comprising at least four lines, preserved on the entrance tympanum of the porch adjoining the monastic church in the south.

Translation: In the year 401 (952) of the Armenian calendar …Tiran…

Another donation inscription which fully shares the writing style of the aforementioned ones can be discerned inside a cut-in-rock hall located north-west of Tzarakar and ending in a concha (it is decorated with a cross):

Translation: May Lord Jesus Christ have mercy. Amen.

Further history of Tzarakar is elucidated by pieces of scanty information reported by Armenian historiographers. In 1028 the monastery was renovated and made suitable for serving as a castle. In 1029 it is mentioned in connection with some construction activity unfolded there by Prince West Sargis. Kirakos Gandzaketsi writes the following about the work unfolded in the late 1020s: “In his day the very distinguished Vest Sargis, after building many fortresses and churches, built the glorious monastery of Xts’konk’ and a church in the name of Saint Sargis; and making Tsarak’ar monastery a fortress, he built stronger walls and glorious churches in it.” Information relating to this building activity is also reported by Mkhitar Ayrivanetsy.

The next record dates from 1178, when Turkish conqueror Gharachay took Kechror and the fortified monastery of Tzarakar: “On the same day, he took Tzarakar from some thieves on the order of Emir Gharachay of Kechror and sold it to Khezelaslan for much gold. And he settled it with dangerous men who did not cease bloodshed day and night until the Christians were exposed to darkness and famine…, with five clergymen being stabbed crosswise.”

In 1182 Gharachay, who still held Tzarakar under his reign, destroyed the renowned Gorozu Cross kept there: “In 631 [of the Armenian calendar] Kharachay, who had conquered Tzarakar, overthrew the cross named Gorozo with a crane…” Within a short time, in 1186 the Armenians of Ani liberated Tzarakar through united forces: “In 635 [of the Armenian calendar] the inhabitants of Ani took the paternal estate of Barsegh (the bishop of Ani), mercilessly slaughtering those who were there, except the women and children.”

The sources of the subsequent centuries make almost no mention of the monastery. However, taking into account the fact that prominent poet and worker of education Khachatur Kecharetsy was buried there in the 14th century, we can suppose that it actively continued its existence between the 13th and 14th centuries. Presumably, Tzarakar was finally ruined between 1829 and 1830, after the mass displacement and emigration of the local Armenian natives.

Architecture

The only surviving parts of Tzarakar Monastery are those of its structures which are cut in the rock, and therefore, are difficult to destroy, whereas the others have been irretrievably lost. For this reason, at present the complex is considered as only a cut-in-rock one consisting of 6 chapels and a main cruciform church with a pseudo-dome surrounded with annexes.

The plan of Tzarakar Monastery and the mountain facade overlooking the south measurement and graphical design by architect Ashot Hakobian, 2010

The plan of Tzarakar Monastery and the mountain facade overlooking the south measurement and graphical design by architect Ashot Hakobian, 2010

It is evident that the rock into which the monastic structures were cut is quite friable, and for this reason, it was found expedient to cover the walls with a layer of plaster to make them solid enough to bear mural paintings and inscriptions.

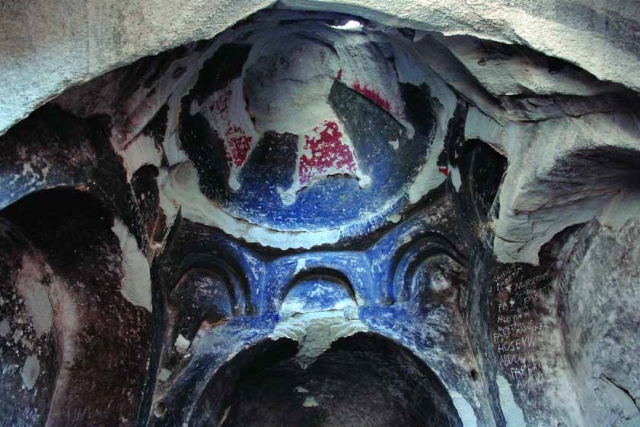

The next cut-in-rock structure which comes second to the main church by its dimensions stands near the south-western corner of the latter. It almost shares the composition of the first church, but it is smaller. Its only entrance, which opens from the east, also serves as a means of communication with an adjacent hall. The structure is illuminated through its only window opening from the south. The chapel shares the decoration of the church: a relief of an equal-winged cross, covered with red paint, adorns the central part of the semi-circular concha, which joins the underdome square through squinches. Reliefs of equal-winged crosses were wide-spread in many other districts of Armenia and can be found in numerous monuments of the early Christian period. Such reliefs were carved throughout the Armenian Highland after the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of Armenia.

The hall situated between the church of Tzarakar Monastery and the chapel of its south-western corner

The hall situated between the church of Tzarakar Monastery and the chapel of its south-western corner.

There is a structure (3.98 x 2.82 meters) between the chapel and the church which serves as an entrance hall for both of them. It is remarkable for its peculiar architectural features: it has an octahedral covering which rests on the intersecting semi-arches of the upper sections of the walls—a similar covering can be particularly seen in monuments of the 9th to 11th centuries, such as Horomos, etc. As a result of continual corrosion, the floor of this entrance hall is at present totally ruined: as a rule, friable rocks rapidly get weathered and slip downwards like sand.

The western chapel/sacristy (3.37 x 1.80 metres) is remarkable for its composition, decoration and architectural features. Its bema is higher than the floor of the prayer hall. It has a cut-in-rock altar rising at a height of 1.10 meter above the floor of the bema. Another cut-in-rock monument of the complex is a chapel located near the southern side of the church bema. Like the other two ones, it may be regarded as the third vestry of the church.

Source: http://www.raa-am.com/vardsk-4/Vardzk-4E.pdf

Bellow more images from the monastery:

The south-eastern entrance of Tzarakar Monastery with the remnants of the inscription of 952 and its plan according to Stephen Sim 1999

The interior of the church of Tzarakar Monastery towards the north-east, south-east, south-west and its north-western squinch

The interior of the church of Tzarakar Monastery towards the north-east, south-east, south-west and its north-western squinch.

The interior of the church of Tzarakar Monastery towards the north-east, south-east, south-west and its north-western squinch.

The concha of the south-western chapel of Tzarakar Monastery; its interior to the sanctuary (north); its north-western squinch and south-western wall pylon

The concha of the south-western chapel of Tzarakar Monastery; its interior to the sanctuary (north); its north-western squinch and south-western wall pylon.

The hall situated between the church of Tzarakar Monastery and the chapel of its south-western corner.

The hall situated between the church of Tzarakar Monastery and the chapel of its south-western corner

Tzarakar Monastery. Partial views of the interior of the chapel vestry standing in the north-east of the church

Tzarakar Monastery. Partial views of the interior of the chapel vestry standing in the north-east of the church

Tzarakar Monastery. Partial views of the interior of the chapel vestry standing in the north-east of the church

Tzarakar Monastery. The ceiling and western wall of the chapel sacristy located south of the sanctuary of the monastic church

Tzarakar Monastery. The ceiling and western wall of the chapel sacristy located south of the sanctuary of the monastic church

Tzarakar Monastery. Partial views of the interior of the chapel vestry standing in the north-east of the church