Betty Londergan

Posted: 09/27/2012 5:04 pm

When I told people I was going to Armenia with Heifer International, the most frequent response was, “Wow, um.. where is that?”

So first, the geography lesson: Armenia is just east of Turkey and bordered by Georgia to the North, Azerbaijan to the East, and Iran to the South. Which basically means Armenia is a raft of Christianity in a sea of Muslim countries. In fact, Armenia was the first nation in the world to adopt Christianity as its state religion in 301 AD, and that has pretty much defined and shaped its turbulent history through the ages.

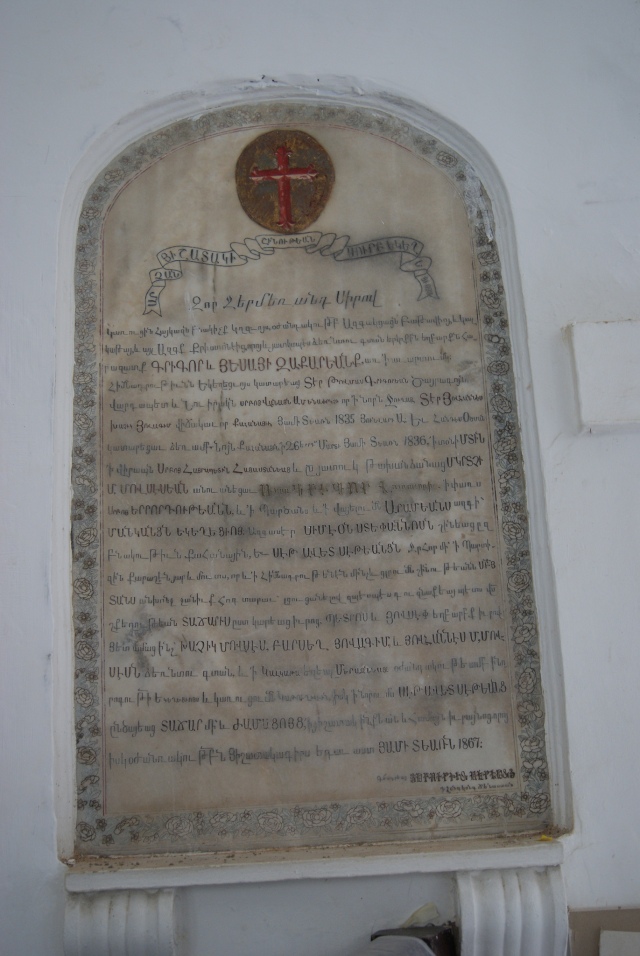

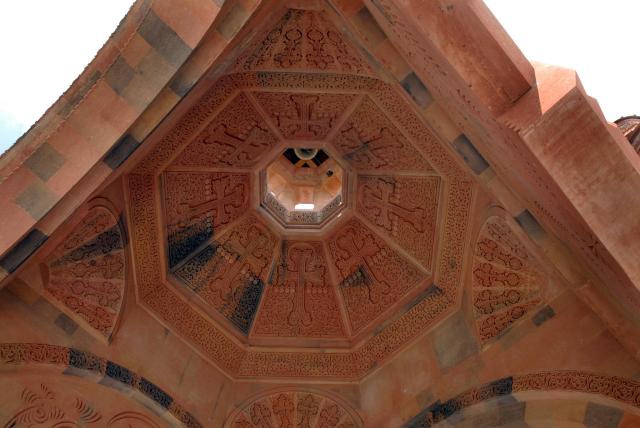

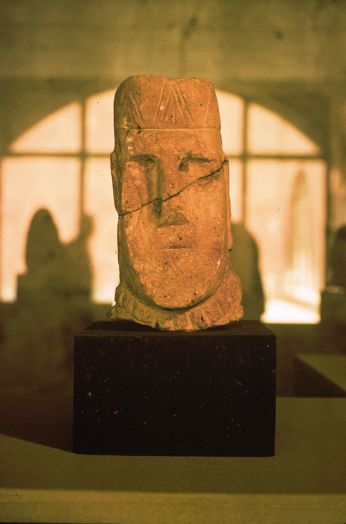

Armenia is a mystical place — filled with monasteries, pagan temples, prayer stones and churches, most tucked away in wildly remote places to protect them from destruction. (It didn’t.) These pockmarked Christian monuments are the pride of Armenia as well as testament to a seemingly endless parade of invaders: conquering Persians, rampaging Mongols, invading Turks, totalitarian Soviets, as well as the ravages of devastating earthquakes. For over 600 years, Armenians knew themselves to be a distinct people and yet were not a sovereign country. Faced with hostility from all sides, Armenians held fast to their identity and managed to survive into the modern era with a faith as deep and constant as the obsidian stone that is part of this beautiful landscape.

Although the Kardashians are undoubtedly the world’s most famous Armenians, they are not typical of the Armenian character (sorry, Kim) — although I did see an awful lot of beautiful women in the modern capital of Yerevan. Actually, it’s a bit hard to get a firm grasp on the Armenian character because it’s full of such deep contradictions.

Armenians are enormously proud, highly educated (with a literacy rate of almost 100 percent), and hospitable beyond your wildest expectations. In centuries of life along the Silk Route, Armenians became known for their business savvy in commerce and trade, and they interacted easily with almost every European and Asian culture. But Armenia’s psyche is indelibly haunted by the memory of great loss (1.5 million annihilated in 1915 alone) and like all the Caucasus’s states, the people have experienced centuries of brutal conflict that staggers the imagination and continues today in the convoluted conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno Karabagh.

Armenia was a part of the Soviet Socialist Republics for more than 70 years, and has only been independent for 21 years. Armenia’s economy was far more robust and productive under Soviet rule, and the country is still struggling to establish a modern economy with almost no natural resources (and with its two borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan closed). While the capital of Yerevan is bustling, elegant and thriving, in the countryside there is little besides subsistence farming to support the villagers and the poverty rate approaches 35 percent. Many men still immigrate to take jobs in neighboring countries; in fact, three times as many Armenians now live outside the country as inhabit it. That’s why Heifer is investing $3.7 million in projects to help the smallholder farmer in Armenia achieve economic independence and food security — and what I came to see.

Despite the economic challenges, Armenia is hardly depressing. For one thing, the country is beautiful. The food is incredible, and though the people are tough (they’ve had to be) they are also joyful, sweet people who love to garden, to eat, to talk and to welcome visitors — particularly if you’re one of the 8 million diaspora Armenians who’s coming back home.

Even their blooming Christian cross never features the crucified Christ, because Armenians believe in the rising– not the suffering.

And that’s as good a prescription for moving forward as anything I can imagine!

A few more pictures bellow!